In the dimly lit bars of Chengdu and the underground music scenes of Guangzhou, a sonic revolution is quietly unfolding. It’s not the familiar chords of Western rock or the polished Mandarin pop that dominates China’s airwaves, but something far more raw and rooted: dialect rock. Here, musicians are plugging in their guitars, pounding their drums, and singing in the local tongues of their hometowns—Sichuanese, Cantonese, Hokkien, and beyond. This movement is more than a musical trend; it’s a cultural reclamation, a defiant act of identity in an era of homogenization.

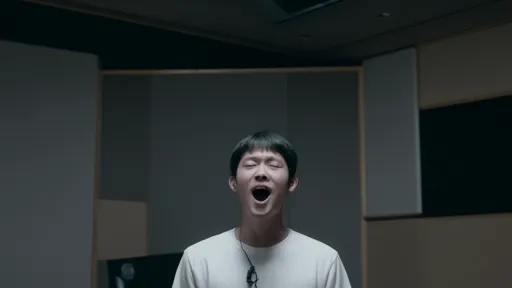

The power of singing in one’s mother tongue is visceral and immediate. For artists, dialect is not merely a linguistic choice but an emotional one. It carries the weight of memory, the texture of local life, and the nuances of colloquial expression that standardized languages often flatten. When a Sichuanese rock band like Mr. Turtle belts out lyrics in the distinctive twang of Chengdu, it resonates with a authenticity that Mandarin cannot replicate. The dialect infuses the music with humor, sarcasm, and a street-level grit that connects directly with the audience’s lived experiences.

This connection is amplified in live performances, where the shared dialect creates an intimate bond between the artist and the crowd. At a dialect rock concert, the atmosphere is electric with recognition—a collective celebration of local identity. Fans shout along to lyrics that reference neighborhood landmarks, local slang, and inside jokes, transforming the event into a communal ritual. For many, especially younger generations who have migrated to cities for work or education, these songs become an auditory anchor to home, a remedy for the loneliness of urban life.

Moreover, dialect rock serves as a vessel for cultural preservation. In China, where government policies have long promoted Mandarin as the national standard, many regional languages are endangered, particularly among the youth. Dialect rock bands, often unintentionally, become archivists of their linguistic heritage. Their songs document the rhythms, idioms, and oral traditions that might otherwise fade into obscurity. In this sense, the music is not just entertainment but activism—a sonic resistance against cultural erosion.

However, this vibrant movement operates within a complex web of challenges. The most immediate is the issue of reach. Singing in a dialect inherently limits the audience. While a band might be legendary in their hometown, they often struggle to break into the national scene. Listeners outside the dialect region may find the lyrics inaccessible, no matter how compelling the music. This commercial constraint forces many dialect rock artists to navigate a tightrope between authenticity and appeal, sometimes leading them to incorporate Mandarin elements or dilute their local flavor to attract a broader fanbase.

Another layer of difficulty is political. China’s cultural landscape is tightly regulated, and lyrics—especially in rock music, a genre historically associated with dissent—are scrutinized. Dialect, with its potential to convey subtext and regional pride, can be viewed suspiciously by authorities. There’s a fine line between celebrating local identity and being perceived as promoting separatism or resistance to national unity. Several dialect rock bands have faced censorship, from having their songs pulled from streaming platforms to being barred from performing live. This creates a chilling effect, where artists self-censor to avoid trouble, muting the very authenticity that defines their work.

Technological barriers also play a role. The algorithms of major music platforms like NetEase Cloud Music or QQ Music are optimized for Mandarin content, making it harder for dialect songs to be discovered. Without promotion, these tracks languish in obscurity, regardless of their quality. Additionally, the lack of standardized writing systems for many dialects complicates lyric transcription and sharing. While Mandarin uses uniform characters, dialects often rely on phonetic approximations or rare characters, creating inconsistencies that frustrate fans trying to engage deeply with the music.

Despite these hurdles, the dialect rock scene is flourishing, driven by passion and a sense of mission. Social media and niche online communities have become lifelines, allowing artists to bypass traditional gatekeepers and connect directly with their core audience. Platforms like Douyin (TikTok) and Bilibili host vibrant subcultures where dialect rock thrives, supported by users who curate playlists, translate lyrics, and organize virtual events. This grassroots energy is the movement’s greatest asset, fostering a resilience that top-down challenges cannot easily extinguish.

Looking ahead, the future of dialect rock may lie in hybridization. Some of the most innovative artists are blending dialects with global genres—mixing Cantonese with electronica or Sichuanese with punk—creating a sound that is both local and cosmopolitan. This fusion not only expands their appeal but also redefines what regional identity can mean in a globalized world. It’s a testament to the adaptability and enduring power of the mother tongue, proving that even in the face of adversity, local voices can find ways to amplify and evolve.

In the end, dialect rock is more than music; it’s a statement. It declares that every language, no matter how localized, has the right to roar through a amplifier, to demand to be heard. It challenges the notion that authenticity must be sacrificed for success, and in doing so, it offers a blueprint for cultural sustainability in the modern age. As long as there are artists willing to sing in the language of their grandparents, and audiences eager to listen, this powerful, dilemma-ridden movement will continue to beat at the heart of China’s underground—and perhaps, one day, far beyond.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025